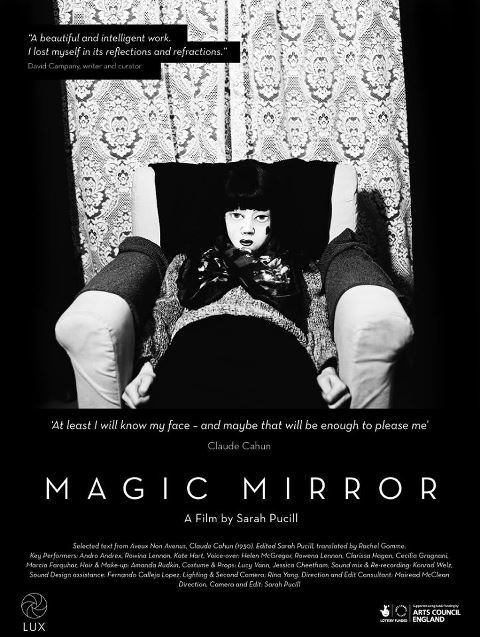

Last Monday I attended the world premiere screening of British artist filmmaker Sarah Pucill’s feature on the text and images of Surrealist Claude Cahun. While I was fully aware of Pucill’s work, I was drawn to the screening primarily because of my own interest in Surrealism and its legacies. Upon arrival at the Tate Modern cinema, it was very pleasing to see a full house (with a queue for return tickets) because I’ve recently experienced quite empty cinemas at both Tate and the ICA (why so few people at the ICA screening of Post Tenebras Lux a month or so ago? ). So yes, a great turnout.

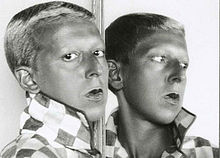

Still taken from Magic Mirror, Sarah Pucill, 2013

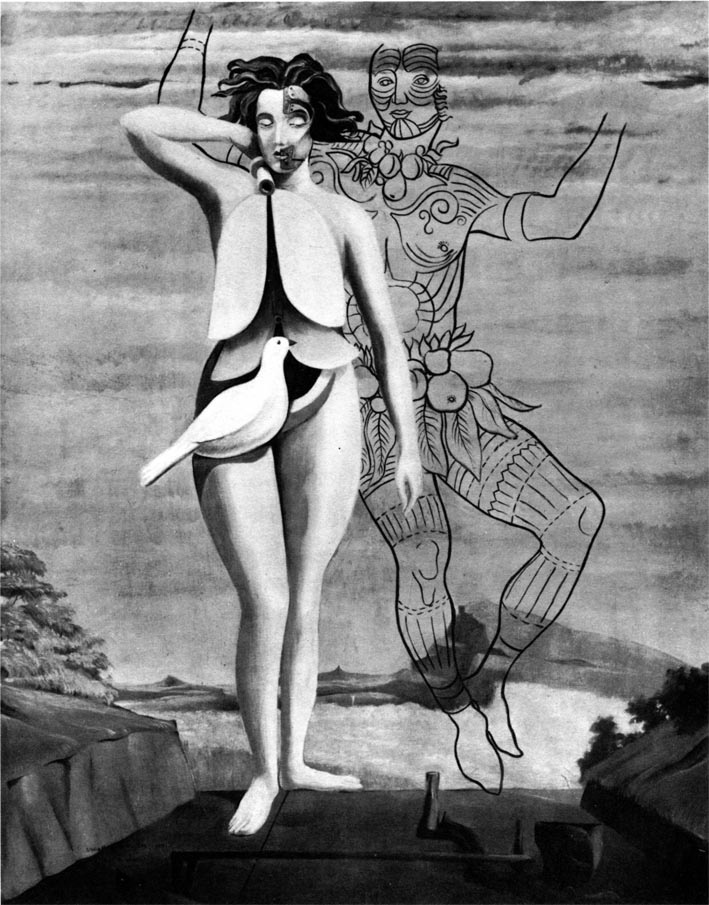

French artist and writer Claude Cahun, (1894 – 1954, née Lucy Schwob) is now well known, her work appropriated by art historians, feminist and queer theorists, who have focused on the imagery in her photographs and its positive transgressions of heteronormative discourse. This was not always the case, and she and her work were largely forgotten until French poet François Leperlier came across Cahun as a somewhat marginal figure in his research for a publication on Surrealism. By all accounts intimidated by Breton’s circle (hardly surprising), Cahun was nevertheless friends with some of the Paris circle, such as Soupault and Desnos, and eventually met Breton in Paris,, photographing him and Jacqueline Lamba as well as contributing photographs to journals such as Bifur (a journal publishing works by former Surrealists).

Jacqueline Lamba and André Breton, Claude Cahun , 1935

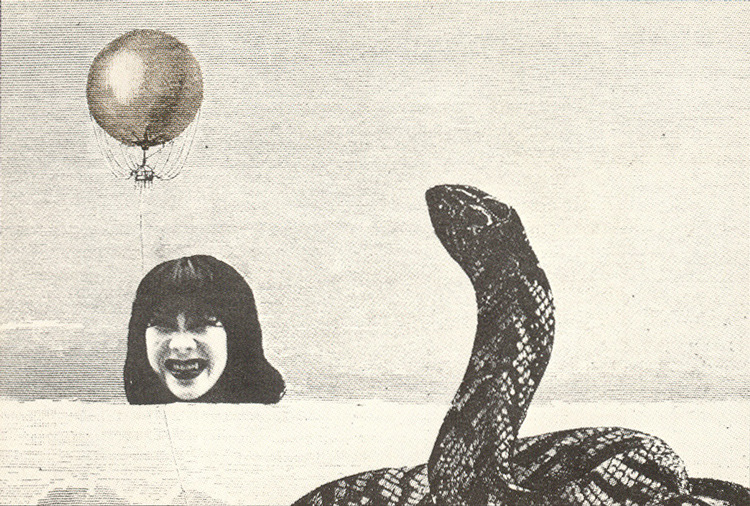

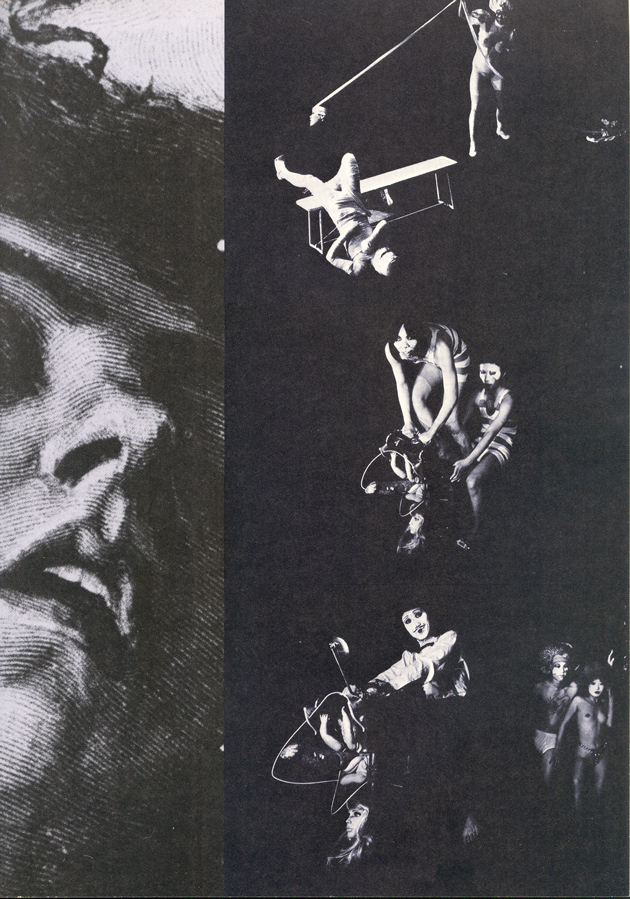

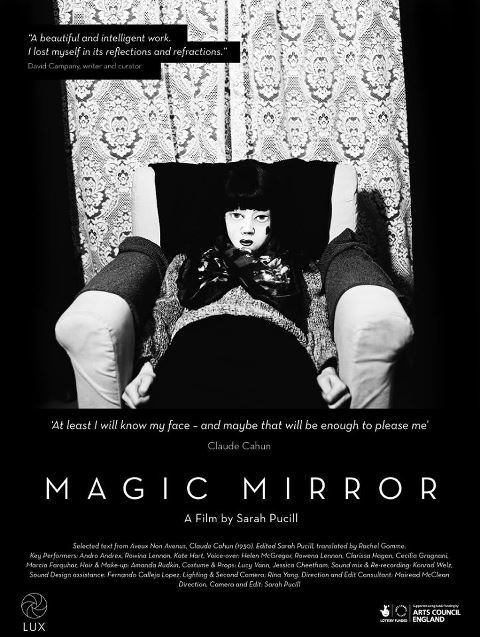

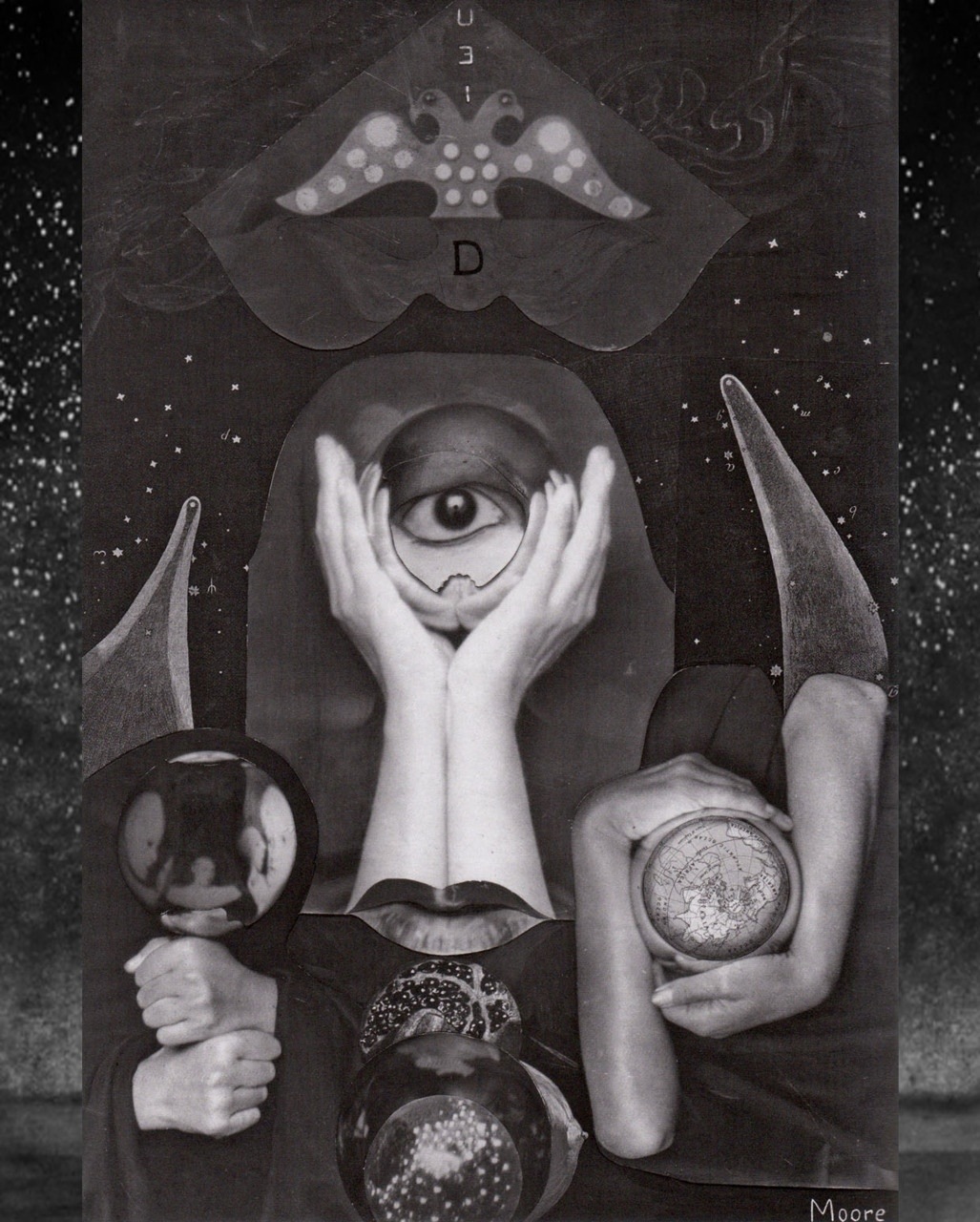

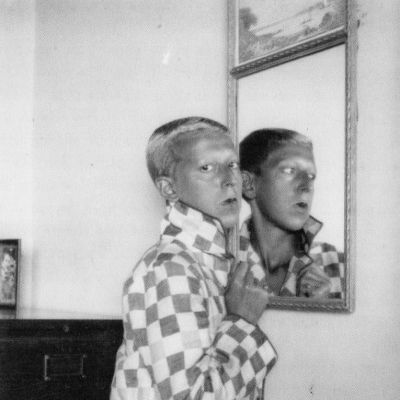

For Pucill, who spoke before and after the screening, Claude Cahun had been on her radar since being introduced to her work as an undergraduate in the 1990s. Pucill feels an affinity with Cahun’s artistic practice and her use of mirroring and fragmentation to explore sexuality and clichés of identification such as the Narcissus myth and self-portraiture. The majority of Cahun’s visual works are self-portraits in which costume, artifice, superimposition, reversals of gender stereotypes, the interchangeability of animate and inanimate objects, mirrors, closeted space, and collage, prevail. Although Cahun is best known for her images, she was a prolific writer, and Pucill explained how her book Avenue non avenues (1930) (published in English as Disavowals, but translated by Pucill as ‘confessions untold’) with its photomontages and heliogravurs served for her (making the film) as an expansion and clarification of the photographs.

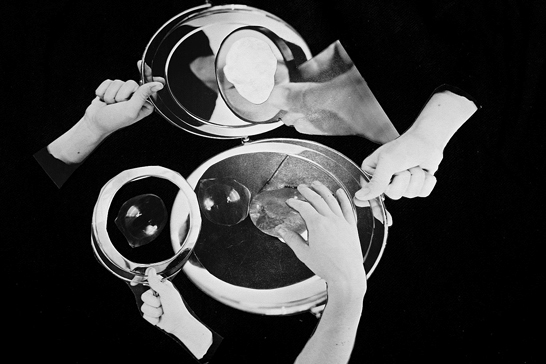

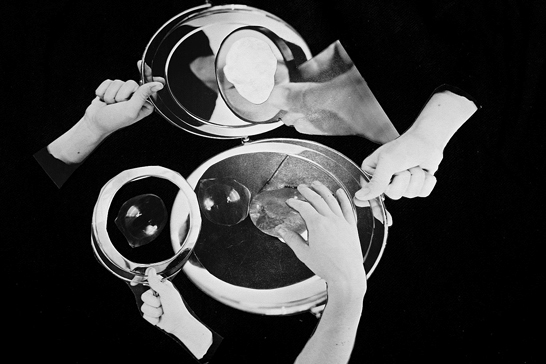

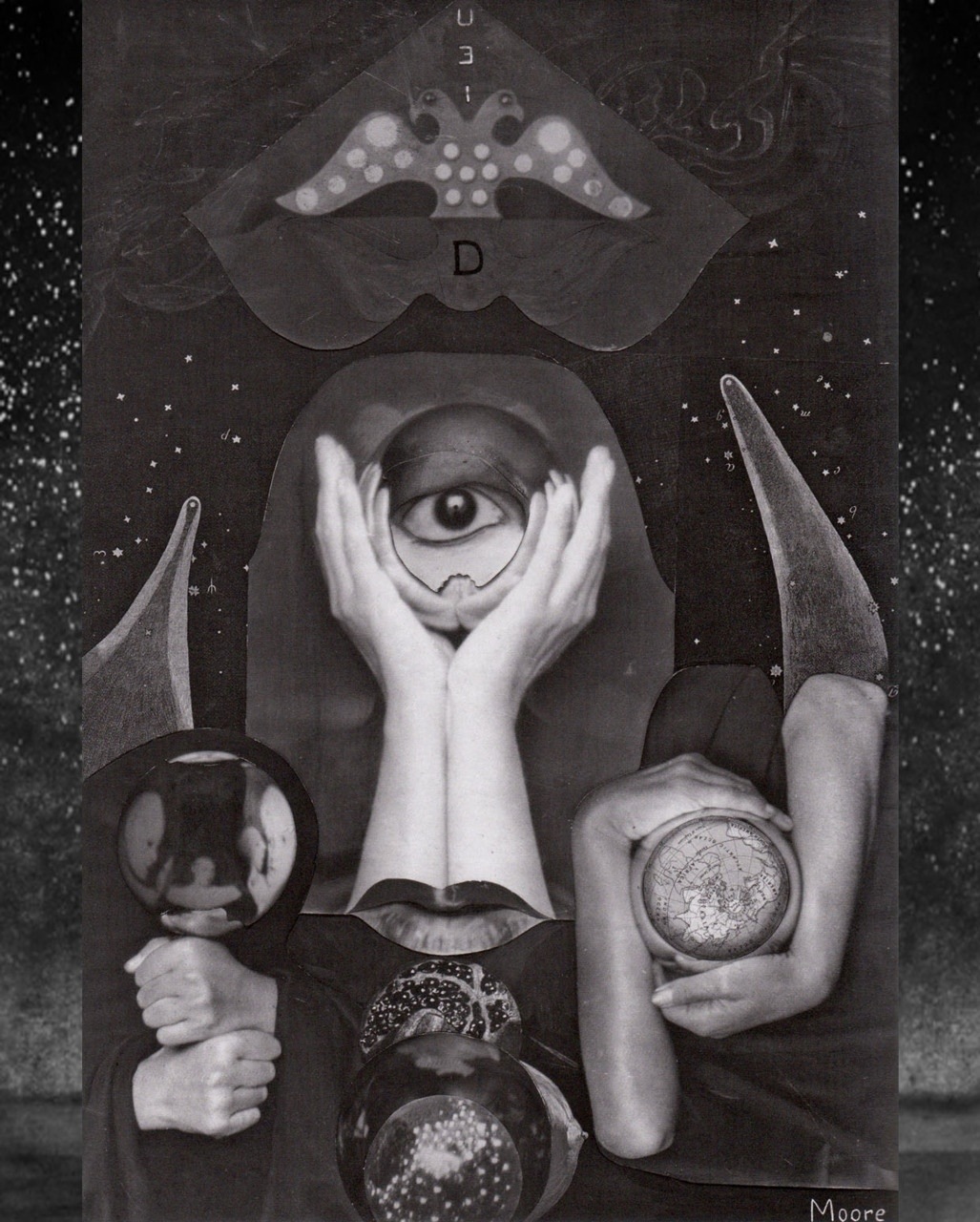

Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore, Phontomontage, Plate 1, Aveux non avenus, 1919 -1929

Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore, Phontomontage, Plate 1, Aveux non avenus, 1919 -1929

Pucill finds Cahun’s obsession with mirrors and other reflecting surfaces such as window glass and water, intriguing, pointing out that the opening words in Aveux non avenus: ‘Sash Window. Glass sheet. Where shall I put the silvering? On this side or the other; in front of or behind the pane?’ bring to the fore questions of self and of reflecting on the self in her film work. The text continues: ‘In front. I imprison myself. I blind myself […] Leave the glass clear, and according to chance and the hours see, confused and partially, sometimes fugitives and sometimes my own look. Then, break the glass panes … with the fragments, compose a stained glass. Byzantine work! Transparency, opacity. What a vow of artifice.’ Dawn Ades notes how this is an overt criticism of Narcissus, of his death, deceived by an image. Cahun understands the artifice, dissolving herself ‘into a never-ending series of masks that have no ‘real’ underneath. These are not so much disguises as adoptions of the socially imposed shells of feminine or masculine identities (like the doll-woman) which need first to be displayed inorder then to be stripped.’ (Ades, ‘Surrealism, Male-Female’, in Surrealism. Desire Unbound, Jennifer Mundy (ed.), 2002, 171-201).

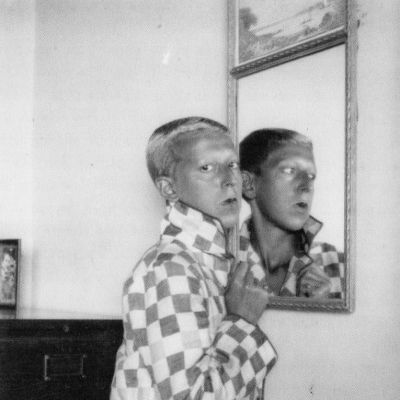

Sarah Pucill, Magic Mirror, 2013

Pucill’s film re-enacts the figures and mise en scene in Cahun’s photographs, creating further uncanny reflections and expansions of the original self that ultimately, for me, seem most akin to the photomontages in Aveux non avenus. More significant to my mind, is the dissemination of the self into a mise en abîme of self-reflexivity, a kaleidoscopic, polymorphous self that travels back and forth between Pucill and Cahun, refusing, unlike Narcissus, to die. Pucill terms this effect, the scattered self.

Self Portrait, Claude Cahun, 1928

It has oft been noted that Cahun’s work anticipated the work of Cindy Sherman, or the critical writing of Judith Butler on the ‘troubling’ parameters of socially ordained ‘gender identities’. Gender and self is, of course, at the centre of her work, and the play of feminine and masculine masquerades, yet Cahun’s work is much more than self portraiture and ‘gender-bending’. Although not a fully ‘signed-up’ member of the Surrealist group, her work exemplifies both Bretonian ideas of convulsive beauty, chance and merveilleux, but also the more abject, ‘primitive’, visceral power of Bataillean philosophy. There is a sinister, abject body that exceeds the images of women manifested in Breton or Soupault’s writing, or Man Ray’s photographs of the female form (for example), and offers alternative female bodies that tell of much deeper, experiential view of reality, and of the horrors of modern life.