In 1982, Chilean filmmaker Raúl Ruiz made the French language film Three Crowns of the Sailor, a voyage into ancient maritime myth, the human unconscious, and the surreality of identity. By his own account, Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s narrative poem ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’, in which an old sailor forces his moralistic tale of supernatural forces onto an impressionable young man, provided Ruiz with material for his own treatise on the human condition.

He holds him with his glittering eye –

The Wedding-Guest stood still,

And listens like a three years’ child:

The Mariner hath his will.

The Wedding-Guest sat on a stone:

He cannot choose but hear;

And thus spake on that ancient man,

The bright-eyed Mariner […]

[…] The loud wind never reached the ship,

Yet now the ship moved on!

Beneath the lightning and the moon

The dead men gave a groan.

They groaned, they stirred, they all uprose,

Nor spake, nor moved their eyes;

It had been strange, even in a dream,

To have seen those dead men rise.

The helmsman steered, the ship moved on;

Yet never a breeze up blew;

The mariners all ‘gan work the ropes,

Where they were wont to do;

They raised their limbs like lifeless tools –

We were a ghastly crew. – Samuel Taylor Coleridge ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ (Published in the collection Lyrical Ballads, 1798)

Ruiz’s shadowy film drifts in and out of the overlapping memories of a sailor who, like Coleridge’s mariner, sets about telling his story to a young student, Tadeusz. The sailor witnesses the young man murder his professor, and prevents him from fleeing the scene (and the country) with a promise to procure him a job aboard a large ship preparing for imminent departure. In return he must pay the sailor three Danish crowns and listen to his story in its entirety. The contingent spontaneity of their meeting seems anything but coincidental, and yet, as in its surrealist incarnation, chance forms the structure that drives this perforated narrative.

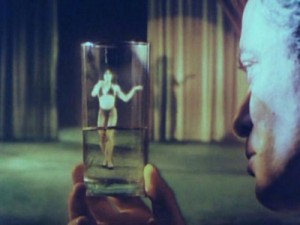

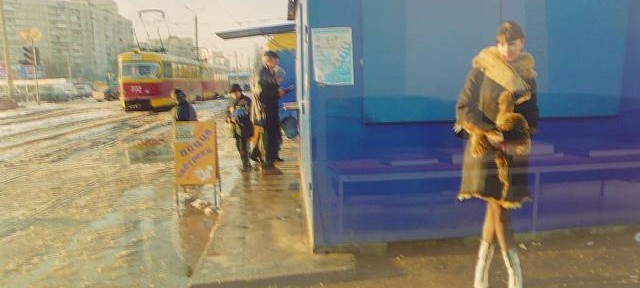

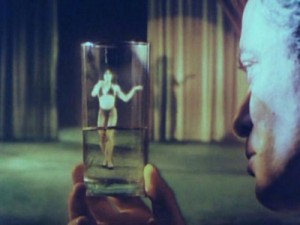

The sailor, a native of Valparaiso – a thriving town used as a stopover by sailors travelling between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans – is haunted by memories of his childhood home and by the expectations of the family whom he has left behind; and although he encounters surrogate family members on his travels, his compass ultimately points home. The spectator is presented with a series of episodes from the Sailor’s past, recalled through what Ruiz terms the colours of a ‘siesta nightmare’ : a mainly desaturated palette which ebbs and flows between the contrastive monochrome of the ‘real time’ scenes shot in Russia as the sailor recounts his tale to Tadeusz, and the strong blue and red contrasts of exoticised ‘location’ memories shot with Agfa film stock. The resulting atmosphere is one of uncertainty, in which the boundaries between the real world and that of the imagination, or the supernatural become increasingly indiscernible. In his recounted history, the sailor is the only living protagonist on a ship of ghosts. Crew members die only to be resurrected, and Ruiz emphasises the exchange value of human identity by constantly underpinning the eternal return of history in which an individual is but flotsam at sea. The characters often repeat the refrain “It’s not me. It’s someone else’ when the sailor attempts to grasp their identity – an absurd exchange that confounds him. Finally he realises that he alone is ‘different’ among these interchangeable ghostly bodies, because he is still alive. And yet the fate of death, of becoming a fragment in the unconscious discourse of history, will not elude him either. This is not a film with an ending,and, unlike Coleridge’s poem, does not offer moral guidance. It is a film about return, and thus, the recurrent human intrigue in what lies beyond.

For me, two aspects of this film are intriguing: firstly Ruiz’s own allusions to a literary heritage in which supernatural, folkloric, mytho-poetic events are narrated, and secondly the application of what Ruiz terms ‘bricolage’ (from Picasso) – to use whatever materials and media are to hand – to create cinema. Drawing from both classical and avant-garde sources, Ruiz’s film presents stories, vignettes, and visual traces of disparate cultures that all point to the same conundrum – how do we experience reality as an individual, an individual that is already a composite of layers and layers of history? The direct approach is to break down and disrupt narrative through fragmentation.

In the first volume of his Poetics of Cinema (2005) Ruiz writes a compelling analysis of film that refutes the ‘central conflict’ structure beloved of Hollywood screenwriters in which narrative is driven by establishing and resolving conflict. Rather, he believes, a film must consist of a myriad of ‘micro-actions’ that may or may not have a relation to the ‘main’ action. Moreover, he argues that within the diegetic world of a film is a hidden, or secret, film that unfolds simultaneous to the viewing experience, shaped by a spectator’s apriori experience and knowledge of other worlds, other films. Rather than beginning with a symbolic motif to mark the ‘conflict’, Three Crowns commences with a murder that is not followed through, and ends with another murder that does not resolve, but echoes this action. The killer’s motivation is not explored, neither is his punishment or his actual escape. His presence triggers the storytelling and ends it. As Ruiz explains, the departure point for an idea, or a scene is an image-situation: ‘The image-situation is the instrument that permits the evocation or the invocation of the imaged beings. It serves as a bridge, an airport, for the multiple films that will coexist in the film that is finally seen.’ (Ruiz, The Poetics of Cinema Vol. I, 2005, 116) The murder evokes thousands of real and screen murders, and it invokes the possibility of more to come, for Ruiz the action is generated in the constant back-and-forth between what has happened and what could possibly happen, the constant pain of thought. “What’s life?” a nameless character asks rhetorically, “It’s just an absurd wound!”

As Surrealist critic Michael Richardson has pointed out, Ruiz is a master of filming objects, ‘respecting their integrity’ and giving them a life force that is not merely tied to the libidinal desires of the protagonists. In Three Crowns religious icons and childhood objects are imbued with an uncanny sense of autonomy, charging the diegetic spaces with additional layers of hybrid historicity. The sailor’s recounting of his travels is pure automatism, and Ruiz encourages the geographical and cultural breadth of these hazily pictured voyages to spark associations with objects to create dynamism.

Finally, hierophany – the breakthrough of the sacred into the everyday world – is a standard concern in Ruiz’s work. In religious discourse, manifestations of gods is given purpose and reason within the cultural bounds of a given social reality, yet the illumination of the supernatural is more often criticised and termed irrational. Three Crowns questions the supernatural beliefs of the sailors, the myths of storytelling, of Coleridge’s poem (based on a neighbour’s dream), and the vivid imagination needed to create meaning from these convergent strands. Ruiz explains that his films are designed to go beyond the limited, moving from one world to another, playing with the four levels of medieval rhetoric : literal, allegorical, ethical, and anagogical (spiritual or mystical interpretation). Non-existent events, he says, are closer to reality because they may happen, they have the potential to happen, they seem real. Real events are dying, in contrast. They have already happened.

We can see in Ruiz’s film something of the magic realism that Jorge Luis Borges notes in Edgar Allen Poe’s colonial sea-horror ‘The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym':

‘A quite different sort of order rules […] , one based not on reason but on association and suggestion – the ancient light of magic.’ (Borges, ‘Narrative Art and Magic’, in Monegal and Reid (eds.), 1981, 37)

It is such a joyous celebration of irreverence, an act of self-critique and parody intended to preempt the criticism the artists knew would inevitably be levelled against them by the art establishment and public alike. Indeed Gilbert and George were censored throughout their early career, and I know for a fact that my print of Fuck from their Dirty Words exhibition at the Serpentine makes some people uncomfortable. Despite their static capture in these photographs, the pair seem so much more animated than in later ‘living sculptures’, which are paradoxically undynamic.

It is such a joyous celebration of irreverence, an act of self-critique and parody intended to preempt the criticism the artists knew would inevitably be levelled against them by the art establishment and public alike. Indeed Gilbert and George were censored throughout their early career, and I know for a fact that my print of Fuck from their Dirty Words exhibition at the Serpentine makes some people uncomfortable. Despite their static capture in these photographs, the pair seem so much more animated than in later ‘living sculptures’, which are paradoxically undynamic.