I really love the effect of the what I shall call the ‘decaying’ mirror in Raul Ubac’s photo portrait. Daido Moriyama applies a similar technique in his self-portraits using reflective surfaces. The erasure/disclosure of the image plays with the solidity of ‘identity’ as a knowable concept. Here, the woman’s head seems to emerge from water, the neck visible below a filmy surface. The bright dots suggest astronomical constellations. The eyes closed, or cast downwards, the face withdraws from the viewer; the filmy, cracked ‘overlay’ removes the subject further accentuating the construction process of the print. The distancing plays with the ‘present’ moment of the photograph, wrapping the female face in a temporal indeterminacy, the patina suggestive of damaged nostalgic snapshot keepsakes from the turn of the nineteenth century. The woman herself, is positioned indeterminately, submerged in the dreamy water of sleep, or imaginative revelry. Significantly, Ubac’s portrait is the image used for the cover of Rosalind Krauss’s The Optical Unconscious, a book which proposes an alternative history of modernist art. Krauss’s book discusses art (such as that by Ubac and Ernst) as the unconscious ‘side’ of modernism, of art detached from the socio- economic, of more radical, fantastic works representing a shifting reality.

Murals Discovered at Former Home of German Artist Otto Dix – SPIEGEL ONLINE

Pasolini for the New Generation – Page – Interview Magazine

Gnostic Dualism and Gender in Baruch « Invocatio

A really interesting blog about Western esotericism that I have just followed. ‘Magic’ is part of my studies after all!

Photos From Expo 70 – Osaka

All hail Okamoto Taro.

And here are some fantastically clear shots of the West German Pavillion.

Photos From Expo 70 – Osaka, Japan of the West German Pavillion where Stockhausen performed daily.

Bohemian exoticism and the Ballets Russes – Ezra Pound’s satirical ‘Les Millwin’

Sonia Delaunay, Costume for ’Cléopâtre’ , Ballets Russes, c. 1918

In the early twentieth century British modernists such as Ezra Pound and Wyndham Lewis scorned and satirised the oriental exoticism prevalent in the Ballets Russes productions that were becoming increasingly popular among the upper classes. These productions became associated with a ‘High Bohemia’ and decadence, and were deemed ‘regressive’ by the avant-garde, owing more to Victorian aestheticism than modern aesthetics. Pound’s poem ‘Les Millwin’ refers to Michel Fokine’s ballet Cléopâtre, which was first brought to life in London in 1911 by Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, with elaborate stage sets and costuming that delighted audiences. The Millwins immortalised in Pound’s poem were , for the poet, typical of the wealthy aristocrats who attended these spectacles.

LES MILLWIN

The little Millwins attend the Russian Ballet.

The mauve and greeenish souls of the little Millwins

Were seen lying along the upper seats

Like so many unused boas.

The turbulent and undisciplined host of art students –

Was before them.

With arms exalted, with fore-arms

Crossed in great futuristic X’s, the art students

Exulted, they beheld the splendours of Cleopatra.

And the little Millwins beheld these things;

With their large and anaemic eyes they looked out upon this configuration.

Let us therefore mention the fact,

For it seems to us worthy of record.

Mieke Bal and Michelle Williams Gamaker’s ‘Sissi in Analysis': Transference, Trace, and Museum Space.

‘Sissi’ in Issey Miyake

Installations at the Freud Museum in London are always creepy in part (Freud’s ‘spinal’ armchair and replica oral prosthesis are the stuff of horror films,) but I can’t think of a better setting to augment the psychological content latent in such works as Louise Bourgeois’ bronze sculpture ‘Maman’ (which was housed in the museum’s garden earlier this year). The museum itself provides an intimate, secretive space that charges exhibits with affect and underscores the art-science problematic central to psychoanalysis itself and the source of much critical consternation in readings of Freud’s work.

Mieke Bal and Michelle Williams Gamaker’s ‘Sissi in Analysis’ is a ten-screen video installation that ‘fictionalises’ the analysis of a real patient taken from a book entitled Mère Folle by the French psychoanalyst Françoise Davoine.The ten screens were set on various surfaces in rooms throughout the museum, sharing space with Freud’s own paraphernalia and other historical objects related to the history of psychoanalysis. Much like Freud’s most famous case study of female ‘hysteria’ in which the female patient Ida Bauer, or ‘Dora’, voices the physical and mental violations that her parents and a neighbouring couple inflict on her, Davoine’s was a failed analysis of a young woman (both Freud’s and Davoine’s patients cancelled their analysis mid-way through).

Sissi, in contrast to Dora, however experienced a greater severity of physical suffering, undergoing an abortion after being impregnated by her father which resulted in her being sterilised without her consent. In both cases the mother conspires to cover up for the male characters, adding to the complexity of the trauma. Bal and Gamaker’s installation stresses the significance of the witness in the pain of others, and the role of transference in the ‘talking cure’. In ‘Sissi in analysis’, Sissi performs her trauma through dialogue and through her embodiment of a variety of characters for which she changes costume. The filmmakers ‘show’ what Sissi ‘says’, and the spectator becomes a witness in the analytic process. In their statement on the installation, this intent is made clear:

This exhibition is devoted to the idea of a self-discovery that is possible only on the condition of finding a witness. This witness will act as the ‘second-person’, a function that defines sociality. Through witnessing and thus acknowledging trauma, a second person can make sayable what could not be said before. Witnessing in psychoanalysis may well be the most important role for the analyst in the face of trauma, and ‘Sissi in Analysis’ asks the spectator to be that witness.

Davoine’s clinical approach conceptualises psychoanalysis as being rooted in the socio-historical, and she incorporates fiction into her work to test hypotheses – fictional realisation of fantasised events provide insight into the analysis itself.Thus ‘Sissi in Analysis’ functions on multiple plateaus, a fictional reinterpretation of an already quasi-fictional account of one woman’s deep traumatisation. Bal and Gamaker’s films serve to problematise the ‘separation between fiction and reality on many levels': Sissi’s dialogue is authentic, her analytical sessions include both real and fantasised elements, the characters are played by actors, the clothes worn in the video are subsequently transported from the video into display cabinets in the museum itself. The films ask the viewer to interpret, to bring these elements into meaning, to ‘hear’.

Film still taken from ‘Sissi Outside’, Bal/Gamaker, 2011

A separate video work entitled ‘Sissi Outside’ (2011) was situated on the first floor, and although designed by the artists’ as a projection of the ‘outcome’ of Sissi’s analysis, it was the film that I saw first when I visited the exhibition. No matter, it could have come at any time during the 10 segments because I was constantly thinking about the escape from analysis and the resolution of trauma as I took in each of the films regardless of the stage of the treatment that I was watching on screen. Thus to me this final coda represented a version of my own fantasy of release for Sissi which remained at the surface as I walked around. According to the artists, the real Sissi did finally escape her confinement. They present this escape in a video of Sissi years later on the island of Seili, walking through the grounds of a former leper colony. Her seemingly aimless rambling appears to have brought contentment or at least solitude (from the voices too?). This site has not been chosen abitrarily,but has been selected by the filmmakers for its historical significance as a former leper colony. They note that it was written in the colony hospital records that patients were required to bring their own coffin as a prerequisite for admittance. This chilling subtext hints at the volatile space that Sissi inhabits, her illness dominating her chance of survival.

The exhibition closed at the end of November, but more information about the wider and ongoing project can be found here.

Citations from the artists taken from Saying It, Mieke Bal and Michelle Williams Gamaker, Renate Ferro, Ocassional Papers, 2012

‘Rising to the Surface’

I am fascinated by Daido Moriyama’s representation of ‘concreteness'; particularly in the emerging images in his 1972 collection ‘Farewell Photography’. Which parts are erased, and which parts take on new life? Temporality is marked by the practice itself, or the viewing, rather than the context.

The moment when the photograph is inside of the developer and under the red light bulb, when the image oozes through and rises to the surface, this is when I most strongly perceive a sense of my own concreteness. Therefore, to me, although the shooting at the actual place is a concrete process, and not just a work of reproduction … it was rather in the dark room, when using hand techniques and when looking at the image as it slowly rose to the surface, that I responded to the concrete impact that “the world never seen before” had on me. It is in the dark room that I can unexpectedly encounter ” a self never seen before”.

Daido Moriyama, Shashin to no taiwa (A Dialogue with Photography), Seikosha, 1995, p.122

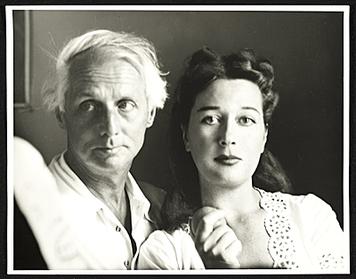

Max and Dorothea

Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning. Today’s inspiration.

Upcoming Gig!

Pantha du Prince is coming to Royal Festival Hall on Friday, 15th February 2013

Here’s a little taster… xx