In her hugely influential article on magic realism in 1920s Germany, the much-cited Irene Guenther examines the emergence of magischer realismus and the political and cultural climate from which it sprang. I was reminded of her work when I read of the incredible uncovering of in excess of 1,500 paintings in the home of Cornelius Gurlitt, the son of Hildebrand Gurlitt (a museum director in Zwichau until ousted by the modern art-loathing Nazi Party), who had been hiding the paintings ever since being declared a victim of Nazi war crimes.

Irene Guenther gives examples of how the Third Reich censored Neue Sachlichkeit artists ‘The left-wing political artists, and, of course all Jewish artists were particular targets of Nazi cultural cleansing (Guenther, Magic Realism, New Objectivity, and the Arts during the Weimar Republic 1995). Numerous painters, including Max Beckmann, Max Ernst, Otto Dix, and George Grosz were denounced as ‘bolshevists’ or ‘kunstwerge’ (art dwarfs) by the Reichskulturkammer (Third Reich’s Chamber of Culture), headed by Joseph Goebbels. Often prohibited from painting and fired from teaching positions, their works were destroyed or displayed for ridicule in vicious ‘Entartete Kunst’ (Degenerate Art) shows or Schandausstellungen (Abomination Exhibitions). Hartlaub was fired from his job as museum director in Mannheim. Roh, accused of being a “cultural bolshevist” was taken to the Dachau concentration camp in 1933’ (Guenther 1995, 55). A few artists’ national landscapes (Schrimpf and Carl Grossberg) proved exceptions and were deemed acceptable to German national pride’ (55).

As a big fan of this era of German painting, it is the idea of Radziwills, Ernsts, Dixs, and Groszs that thrill me with anticipation perhaps even more than possible Matisses and Picassos.

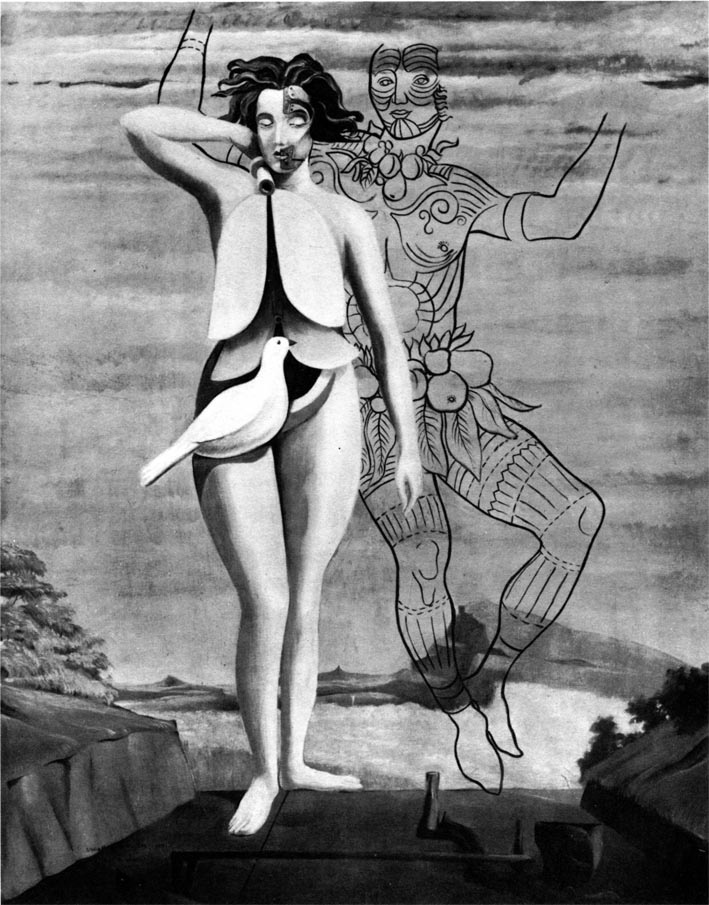

Above is a wonderful shot taken inside the ‘Entartete Kunst’ show which opened in Munich on the 19th of July, 1937, showcasing 650 confiscated paintings frpm 32 museums. Attented by Goebbels and Hitler, the exhibition toured to 12 other cities, framing these works of art as ‘sick’ and degenerate. I particularly love the fact that in the centre of this photograph we see Max Ernst’s fantastical collage La belle jardinière [The Beautiful Gardener]

La belle jardinière [The Beautiful Gardener], 1923, oil on canvas, (whereabouts unknown)

It is an example of Ernst’s ‘overpaintings’ in which he bases drawings on earlier collage works, or alters existing paintings, creating ‘palimpsests that recorded resolutions of contradictions’ (Spies 1988, 55-57).